|

There [Kilkenny], the jail being full, we caused sessions immediately to begin. Thirty-six persons were executed ‘among which some good ones, two for treason, a blackamoor, and two witches by natural law, for that we found no law to try them by in this realm.’ Lord Justice Drury and Sir Edward Fyton to the Privy Council, Calendar of Carew State Papers, (20 Nov, 1578), Vol. 2, p.144. (archive.org/details/calendarofcarewm02lamb/page/144/mode/2up), accessed 11 March 2022. The trial took place on 4 November 1578. With thanks to Irish historian Dr. Coleman Dennehy, author of The Irish parliament, 1613-89, editor of Law & Revolution in seventeenth-century Ireland and Restoration Ireland: always settling and never settled and co-editor with Robin Eagles of Henry Bennet, Earl of Arlington, and his World

0 Comments

Samuel Burke was a free person of color, born in Charleston, South Carolina about 1755. He was baptised and raised in Cork, Ireland, becoming a fluent Irish speaker. Given the circumstances of his birth and upbringing it is likely that he was the son of an Irish man though it has not been possible, as yet, to identify his Irish parent. In 1774 he became the servant of Montford Browne, the royal governor of British West Florida. Montford Browne was the son of Edmund Browne, New Grove, Co. Clare and Jane Westropp of Attyflin, Co. Limerick. Assisting Montford Browne, Samuel Burke became a recruitment officer for the British among Irish-speaking dockworkers in New York. After a time in prison in Hartford Connecticut during the American Revolution, Samuel Burke moved to New York, and married a widow, 'a free Dutch mulatto woman' the owner of 5 Dutch St. He served in the Southern Campaign of the Revolutionary War and was evacuated from Charleston in 1782. In 1783, he was living in Greenwich, London, England and applied for compensation for his military service, and the loss of his home at 5 Dutch St., New York, sustained in the war. He was awarded £20 in full and final settlement of his claim.

1 'Free person of color' was the American term applied to those enslaved people who had acquired their freedom before 1862 therefore the American spelling is used. 2 Ruth Holmes Whitehead, Black Loyalists: Southern settlers of Nova Scotia's free Black communities (Nova Scotia, 2013); Kerby Miller, ‘"Scotch Irish", "Black Irish" and "Real Irish": Emigrants and Identities in the Old South’, Andy Bielenberg (ed.), The Irish Diaspora (Longman, 2000). p.148; Nini Rodgers, ‘The Irish in the Carribbean: an overview 1641-1837’ Irish Migration Studies in Latin America, 5:3 (Nov 2007), p.153. 3 Claims and memorials: Decision on the claim of Samuel Burke of South Carolina 1 Sept. 1783. Great Britain, Public Record Office, Audit Office, Class 12, Volume 99, folio 357 (http://www.royalprovincial.com/military/mems/sc/clmburke.htm) (accessed 30 Apr. 2021). 'Being Sunday my wifes Page the little Tawny Moore was Christened in the church by Mr Bland the minister my son Clifford & Sr Fra. Cobbe being god father and my daughter Anne being godmother'

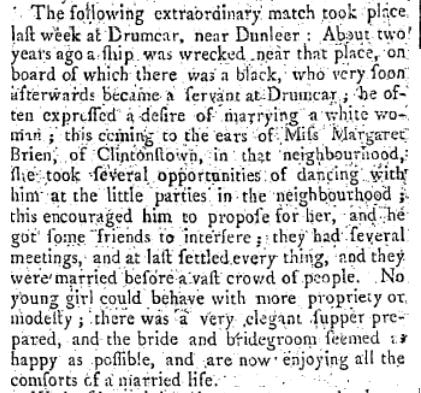

Burlington Diary, Chatsworth House Archive, Lismore Misc MS, vol. 4, 19 November 1665. The Earl, Richard Boyle (1612-1698) and his wife, Elizabeth Clifford Boyle (1613-1691) were regular visitors to Ireland in this period and it is likely her page accompanied her. The baptism occurred in Yorkshire. In 2020, historian Dr. Ann-Maria Walsh recovered the page's name, Carloe and also that he was aged twelve in 1665. Source Walsh, Ann-Maria, The daughters of the first Earl of Cork: writing family, faith, politics and place (Dublin & Chicago, 2020), p. 104. With thanks to Irish historian Dr. Coleman Dennehy, author of The Irish parliament, 1613-89, editor of Law & Revolution in seventeenth-century Ireland and Restoration Ireland: always settling and never settled and co-editor with Robin Eagles of Henry Bennet, Earl of Arlington, and his World Sources Freemans Journal 21 Apr. 1785. Hart, W. A., 'Africans in eighteenth-century Ireland' in Irish Historical Studies, 33:129 (May 2002), pp 19-32. Many thanks to Irish historian Dr. Coleman Dennehy, author of The Irish parliament, 1613-89, editor of Law & Revolution in seventeenth-century Ireland and Restoration Ireland: always settling and never settled and co-editor with Robin Eagles of Henry Bennet, Earl of Arlington, and his World

1613 Extract from a letter written by Jesuit priest John Bushlock to the Superior General of the Jesuits, Claudius Aquaviva regarding the Jesuit mission to Ulster in 1613. 'To the bosom of holy Mother Church, two men were added, the conversion of one of whom must certainly not be kept in silence. This man, Indian by nationality (Hic natione Indus), was captured as a three-year-old boy by an English pirate. Hence, in the custom of heretics, he imbibed the errors of Calvin from earliest childhood to such a degree that later as an adolescent he did not think of practicing a religion other than his own sect anywhere. It happened, however, with God permitting, that he stole twelve gold coins from his master and was thus put on trial for his life before judges. But when the matter was understood, our priest managed to get the lord to drop the accusation and spare his life. Immediately he grabbed the opportunity and cultivated the man with the teaching of the Catholic faith and after a few days made him, now renewed by baptism, a member of the Church.' John Bushlock, SJ, to the Very Reverend Father in Christ, Father Claudius Aquaviva, Superior General of the Society of Jesus, 1613; Irish Jesuit Annual Letters, 1604-1674 edit. Vera Moyne (2 vols, Dublin, 2019), vol. I, pp 325-6. In 2002, historian W.A. Hart identified 160 references, mostly in newspapers and memoirs, to African people resident in Ireland in the period 1750-1799. These findings, he continued, suggest the likelihood that there was 2,000-3,000 African people in Ireland. This number is as large as the number of African people in France which had a population four times that of Ireland in the same time period. The Irish references are tantalising. Many of them do not give a name for the person. Terms used to describe the unnamed person vary: 'blackamoor' 'Black' 'sable-skinned' 'Indian' 'black Negro' 'exotic'. Without Census records we often lose sight of the person. It is not uncommon for researchers to come across references to 'African' or 'Indian' people in Ireland whilst engaged in other research. This blog aims to be a repository for these fragmented accounts. It is hoped that over time it may be possible to uncover the names and fate of these 'African' and 'Indian' people in Ireland. Did they remain in Ireland? At least some of them had families in Ireland. What became of their descendants? There are 1870 Census records in South Carolina which give Ireland as the place of birth of people with the racial designation of Black and/or Mulatto. There is much that we do not know. Contributions are welcome from those who have found these fragments and blogs will be amended if and when further information comes to light. Sources Hart, W. A., 'Africans in eighteenth-century Ireland' in Irish Historical Studies, 33:129 (May 2002), pp 19-32. Brennan, Martine, blog to follow re. African Americans in South Carolina with a recorded birth place of Ireland. |

ContributorsMartine Brennan ArchivesCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed